Human nature and the Truthiness of the photograph - Geoffrey Batchen.

from The Nature of Photography and the Photography of Nature - Joan Fontcuberta

A very recent discovery has been the amazing book called ‘The Nature of Photography and the Photography of Nature’ - Joan Fontcuberta. The book itself is an art work, soft green covering and there is no front or back, as both titles are the right way up. The book covers 6 of Fontcuberta’s most iconic series, including Herbarium (1984).

The first essay in the book is written by Geoffrey Batchen, who teaches history of photography in Wellington ,NZ, who also is a writer and curator. Through this essay Batchen describes how Fontcuberta tests our faith and trust in the process of photography in his work.

Truthiness, according to Stephen Colbert, is “what you want the facts to be, as opposed to what the facts are’.(pg 5) The dictionary describes it as ‘the quality of seeming to be true according to one's intuition, opinion, or perception without regard to logic, factual evidence”.

Geoffrey Batchen sees truthiness as ‘a serious joke, a joke about truth and falsehood that is itself a lie, a lie one tells in order to reveal a greater truth that lies beneath it’. (pg 5)

He describes Fontcuberta’s work as a creative mix of fact and fiction, science and art. He goes further and points out that Fontcuberta exploits our trust and belief in photographic imagery. He exploits our desire and faith to believe that what we see in a photograph to be truth.

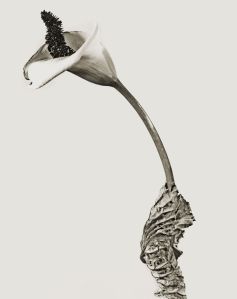

In his series titled Herbarium, Fontcuberta presents the viewer with a series of ‘botanical’ images, where each image has a Latin classification, this inclusion of the Latin name completes for the viewer the codes of botany, creating a sense of truth about them.

This suggestion of the image being a photograph of a ‘real plant’ discourages closer examination. But when the images are closely examined “they are not only not what they appear to be; they are exactly the opposite of what they appear to be”.(pg 6)

While reading this essay question such as; Does the viewer feel tricked? Do they question their belief and truths once they discover the ‘truth’ of these works? Answer I don’t have, but can imagine that some viewer will feel duped, while others may laugh at their own gullibility

Photography has many mysteries and also emotive responses, one mystery is that ‘a well made photograph could easily be mistaken for the thing itself, confusing that most essential of differences, the one between reality and its representation.’ (pg 6)

This confusion started at the conception of photography, where Talbot’s first contact print (‘directly taken from a piece of lace itself’), which was a picture of a piece of white lace, was actually the negative of the original lace.

So what looked like the real thing was actually a negative of the real thing. What is interesting to note here is that a ‘positive ‘ can be taken of this negative (again through a contact print method). But this ‘positive’ would be black. This whole positive/negative talk alone creates confusion of what is real and what is a copy of the real.

What a photograph does do, it certifies that something was present in front of the lens at some point in the past space and time. What the photograph does not do, it does not record truth to appearance, as it can’t be trusted that the image you are observing is genuine (Something we are now much more aware of in the digital age)

Fontcuberta challenges this perception with his Herbarium series very well; As the images appear to depict flowers, they represent ‘botanicity' (pg 7 - a term coined by Batchen to describe the visual conventions of botanical study and the authority of science they conjure, and with it the truthiness that makes botany plausible as a body of evidence.’)

Fontcuberta’s ‘botanicity’ images play both with the faithful recording of a ‘plant’ and the recording of a symbolic representation of a ‘plant’. These images are further loaded with the fancy nomenclature and representational display closely linked to botany. These added layers create a sense of truth and through that ‘truth’ the viewer want to believe these. Fontcuberta further strengthened the ‘authenticity’ by providing field notes and collection data of these plants.

Photographic history is filled with deceptions, much of it happened (and happens) at the development stage. A gentle removal of a blemish in the wrong place or a smoothing out of the complexion. Or as Edward Steichen in 1903 wrote in an essay titled ‘Ye Fakers’: ‘In the very beginning, when the operator controls and regulates this time exposure, when in the darkroom the developer is mixed for detail, breadth, flatness, or contrast, faking has been resorted to. In fact, every photograph is a fake from start to finish, as purely impersonal, unmanipulated photographs being practically impossible.’ (pg 26)

What is different with Fontcuberta’s Herbarium series, it that it started its deception of truth with the content that was photographed. As the ‘plants were made’ using many composites, for example actual plant material, feathers, painted paper. Only close observation & questioning opens this door to the viewer.

What Fontcuberta asks us to do is also think as much as to look. (pg 26). Acceptance of the content of an image on its visual symbolisms only proves that we can see, but also that we are blinded by ‘knowledge’. Because to look at his photographs is to put aside questions about what is true and challenge more what is right. (pg 27)

Batchen has summed it up much better than I could do in this essay;

‘We trust in photographs because they are taken to be an indisputable trace of something that once existed in the world. This trace both confirms the reality of that existence and remembers it, potentially surviving as a fragile talisman of its presence even after the person or thing depicted has passed on. In other words, we submit ourselves to photography to deny the possibility of death, to stop time in its tracks and us with it. But this promise of immortality comes at a price - the suspension of our critical faculties, the surrender of those faculties to faith. We are asked to adopt a belief in the capacities of photography that chooses to overlook its various artifices in the interest of securing for ourselves a life everlasting. This is why we so tenaciously invest our faith in photographs; our (after) lives depend on it. (pg 27)

After reading this essay I started to think: Is this why I use a camera the way I do?

I float between the real and the unreal in my work, as many of my images are, just like Fontcuberta botanicity, they look like plants or at least plant material. But the plant/plant material has been manipulated in some way, either at the set stage or in the development stage or have become a blend of processes.

Without knowing about Foncuberta’s practice when I ‘filled my bottles with plant pieces’ (the ‘Cabinets of Curiosities’ series), I deliberately practiced deception. Creating belief that I had rows of bottles filled with all types of plants. My images were based on trickery, this was strengthened through the general knowledge that science preserves items of botanica.

Trickery was also used in creating both the ‘Gatherings’ - ongoing series and the ‘Shifting Sight’ series.

My muse are plants and not unlike Fontcuberta or Blossfeldt (to discuss in next blog) I manipulate these plants. I too want the viewer to look and question? I believe that ‘we see, but we don’t see’. Just like Fontcuberta I want the viewer to think at what they are looking at.

My work is filled with truthiness, positives and negatives, real and unreal. Further thinking required here.

References for Image:

Image 1. : http://irenebrination.typepad.com/irenebrination_notes_on_a/2013/10/joan-fontcuberta.html