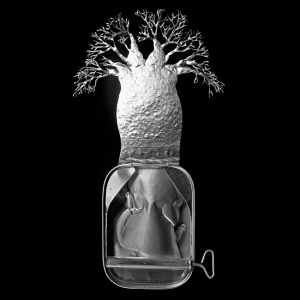

It appears to be hard to get away from any sexual references when dealing with plants, not really surprising, considering that flowers are the sex organs of plants. As an artist I currently have no desire to include any erotic imagery in my work, but this does not mean that I do admire those who do it and do it well. And one such art work is Paradisus terrestris (1999) by Fiona Hall.  Nelumbo nucifera; nelum (Sinhala); thamereri (Taml); lotus, 1999, aluminium and steel. Image courtesy of the artist The parts of this work that pulled me in were the exquisitely crafted plant specimens. And my ‘naive self’ for a long time did not see the erotic imagery inside the sardine tins. Once I ‘discovered’ them, I for a long time, could not enjoy the work as much as I had before this ‘discovery’. Since reading the book Fiona Hall by Julie Ewington, Chapter 3 Sex and Gardening, my admiration for the work has returned (funnily enough, it has not changed my prude view of these images). As it is a series/work that has many layers in it, as I discovered from this book and also the bookfiona hall - force field (which was published in conjunction with an exhibition at Museum of Contemporary ARt in Sydney and City Gallery in Wellington). The works in this series especially challenges people, in regards to what is appropriate to view outside the safety of our home/bedroom. As said before my reaction was certainly one of surprise (I can now giggle about that). The work can very simply be described as: Botany, Sex & Language. All 3 elements are present in the work, and for me all have same visual weighting. Pulling the title apart first: Looking at this work you (I) first notice delicately crafted plants out of tins, this is theParadisus part of the series. These plants are attached to sardine tins, in which erotic images appear, this being theterrestris part of the series. The addition of language is through descriptive botanical labels, these contain both the Linnaean Latin classification and the English common name - providing a level of scientific ordering, but by adding the common name, Hall has made the work accessible to all, not just ‘scientific gardeners’. Ewington also included this table in the book; ‘The work can be described as the following schematic way:

Nelumbo nucifera; nelum (Sinhala); thamereri (Taml); lotus, 1999, aluminium and steel. Image courtesy of the artist The parts of this work that pulled me in were the exquisitely crafted plant specimens. And my ‘naive self’ for a long time did not see the erotic imagery inside the sardine tins. Once I ‘discovered’ them, I for a long time, could not enjoy the work as much as I had before this ‘discovery’. Since reading the book Fiona Hall by Julie Ewington, Chapter 3 Sex and Gardening, my admiration for the work has returned (funnily enough, it has not changed my prude view of these images). As it is a series/work that has many layers in it, as I discovered from this book and also the bookfiona hall - force field (which was published in conjunction with an exhibition at Museum of Contemporary ARt in Sydney and City Gallery in Wellington). The works in this series especially challenges people, in regards to what is appropriate to view outside the safety of our home/bedroom. As said before my reaction was certainly one of surprise (I can now giggle about that). The work can very simply be described as: Botany, Sex & Language. All 3 elements are present in the work, and for me all have same visual weighting. Pulling the title apart first: Looking at this work you (I) first notice delicately crafted plants out of tins, this is theParadisus part of the series. These plants are attached to sardine tins, in which erotic images appear, this being theterrestris part of the series. The addition of language is through descriptive botanical labels, these contain both the Linnaean Latin classification and the English common name - providing a level of scientific ordering, but by adding the common name, Hall has made the work accessible to all, not just ‘scientific gardeners’. Ewington also included this table in the book; ‘The work can be described as the following schematic way:

| plant | natural world | botany | distance | paradise |

| bodies | human beings | sex | proximity | earth |

| text | society | classification | commentary | knowledge |

(Ewington,2005 pg 101) This table is a very apt way of describing these works in words. The only column I am not entirely in agreement with is the last, as personally would swap the description of plant and bodies around - plants are after all from the earth, while our bodies are not literally from ‘mother earth’ but we do/can enter into paradise with them. The plants chosen for this works were associated with ideas of paradise and the divine, the exotic or artistic suggestive associations. They were selected from botanical publications. Plants such as banana palm is certainly an obvious plant from paradise.  The erotic imagery inside the tins is “sex, is not romance. It is sex, both straight and bent, playful and delightful, enjoyed in complete innocence”. The tins “unlock to reveal rank delights of everyday life.” (Ewington pg 102) As Ewington say’s “it presents sex unembellished, with the lights full on”, which for some viewers can be a bit confronting. (Ewington pg 102). What is very clever of Hall is the way she has presented these erotic images, they are the intimate part of the work, through the close cropping, the framing, with no faces seen and no indication whose hands are enjoying the ‘fruits’, male or female. Making these erotic images universal to all, male & female, straight or gay, we, the viewer can picture ourselves in this. It is this aspect that I believe creates the discomfort to the viewer, possibly an acknowledgement of ‘indulging’. Paradisus terrestris compels us to sin together in broad daylight, in public and once you get over the shock, you start to question why she has chosen certain plants with certain erotic imagery. When you take your time to observe the detail & features of the plants, you discover similar features in the erotic imagery. The text is another layer in the work, it is the only layer that is in real size.

The erotic imagery inside the tins is “sex, is not romance. It is sex, both straight and bent, playful and delightful, enjoyed in complete innocence”. The tins “unlock to reveal rank delights of everyday life.” (Ewington pg 102) As Ewington say’s “it presents sex unembellished, with the lights full on”, which for some viewers can be a bit confronting. (Ewington pg 102). What is very clever of Hall is the way she has presented these erotic images, they are the intimate part of the work, through the close cropping, the framing, with no faces seen and no indication whose hands are enjoying the ‘fruits’, male or female. Making these erotic images universal to all, male & female, straight or gay, we, the viewer can picture ourselves in this. It is this aspect that I believe creates the discomfort to the viewer, possibly an acknowledgement of ‘indulging’. Paradisus terrestris compels us to sin together in broad daylight, in public and once you get over the shock, you start to question why she has chosen certain plants with certain erotic imagery. When you take your time to observe the detail & features of the plants, you discover similar features in the erotic imagery. The text is another layer in the work, it is the only layer that is in real size.

Combining latin and common names Hall has again provided many levels of entry for viewers. Those who can understand latin plant names, instantly recognize know, while the addition of the common name gives others another way into the work. Ewington describes the work as “wandering through Paradisus terrestris as drifting through a garden, at times doubling back, admiring now this, now that, allowing thoughts to rise unbidden. It’s the same dreaming and roaming, the same sort of meditativeness, that real garden license.” (Ewington, 2005. pg 107) That feeling of roaming, allowing your view to move from plant to plant and back again, then taking in the whole picture I understand very well. It is a sign of a great garden, a garden that can pull you in to its details and also give you a coherent broader view. I agree with Ewington that this work does that to. Each plant/tin/text are individual pieces, that are part of a series, without being a specialized scientific collection. It could be likened to a type of Floreligium - a collection of plants for their beauty, not their names/scientific ordering. What is also interesting to observe is the differing scales of each layer, as this creates different positions of the viewer. The plants are miniature to real life, but true to size from the botanical illustrations Hall has used to create them.

This miniaturization creates a feeling of seeing the plants from a distance. (As a plants person it was interesting to note that a cacti was the same size as a large tree, creating a concern for me of proportion.) This miniature sizing makes you want to get close to the object, to view details, but it creates an uncomfortable position when viewing/confronted with the images inside the tins. The erotic images were also same size as where Hall obtained the images from, but through the use of cropping and placing them in the sardine tin, our view has been pulled into these making them very intimate. Standing close to see the plants in detail, suddenly can make you move back when confronted by these intimate images. The text is again the size Hall used to copy them from, but it is the only of the 3 layers that is life-size. Using differing proportions to us the viewer, makes this work operate on 3 different scales for the viewer. Another point about the work is that flat, 2D illustrations have become 3D sculptures, possibly an attempt to recreate what they were before they were flattened onto paper. The use of the tin, makes the works gleam and appear precious, which every plant (in my book) is and so is every human. The title of the work Paradisus terrestris can be translated as ‘earthly paradise’, possibly a place where delight is uncensored, where we can as innocent as the flowers in the field or the apple on the trees.(Ewington, 2005 pg108). A place that was naive, a place before Eve picked the apple perhaps. This work has many layers, but after reading about it, and through that creating a better understanding, the layers are intertwined in a magical way. This chapter has helped me to understand to dig deeper and question associations and interpretations much more.

References used:

Fiona Hall - Julie Ewington (2005) Australia. Piper Press. (this book was published in conjunction with the exhibition The art of Fiona Hall 1988-2005 at the Queensland Art Gallery 19 march - 5 June 2005)

fiona hall - force field. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney & City Gallery, WEllington. 2007 Everbest Printing Co Ltd. (with Articles by varies people.)